The story-telling process often unfolds in isolation, but shouldn’t be an entirely solo act. Before the story reaches the masses, or even just gets in front of a select group of interested individuals, we ought to arrange for at least one additional set of eyes to review our work.

That’s a lesson I learned in June 1986, after a commentary I wrote on the death of one of basketball’s greatest young talents, Len Bias, appeared in my hometown newspaper, the Marshfield (Ma.) Mariner.

Only two days after the Boston Celtics made him the 2nd pick in the NBA Draft, Bias died of a heart attack brought on by a cocaine overdose.

Only two days after the Boston Celtics made him the 2nd pick in the NBA Draft, Bias died of a heart attack brought on by a cocaine overdose.

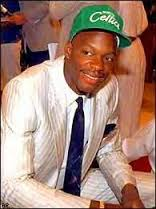

Ten months earlier, along with about 15 other high school basketball players, I shared a cabin with Bias, who was heading into his senior year at the University of Maryland.

Bias was clearly on track to become a superstar in the National Basketball Association when the Boston Celtics invited him to the Red Auerbach Basketball Camp in Marshfield, Ma. As rising high school seniors on our local high school team, my friend Todd and I shared one bunk while Bias was toward the other end of the cabin.

He was at the camp, along with several other college players who worked out and gave pointers to campers.

At the same time, that season’s crop of Celtics’ draft choices and free agents were working out at my high school, on the same court where my competitive career would wrap up in six months.

Our Bias Reaction: Respect, Even Reverence

For so many of us high school players, it was a thrill to be around someone as respected and even revered as Bias. In retrospect, I placed a halo over all that Bias did. As a result, when I related my camp experience the following summer, I inadvertently left out a crucial piece of reporting.

Among the details I included: how Bias had borrowed Todd’s flashlight with old batteries and—what a thoughtful guy!—returned it with fresh batteries; his dominant slam-dunk contest performance at the end of camp; the memory of seeing him read his Bible in bed.

But what I completely blanked on was the memory, on multiple nights, of Bias stumbling drunk into the cabin well past curfew. He would flip on the lights and wake everyone with bellows of “Wake up, you mash-heads!”

(The word sounded like “mash-heads,” anyway… the playful, inebriated slurring of Bias’ voice still rings in my ears.)

More amused than annoyed, a few of us would moan in reply: “Go to sleep, Len!” and then we would all, Bias included, drift off.

Alas, my commentary contained no mention of this side of my weeklong encounter with Bias. When Todd read the piece in the newspaper, he assumed that I decided to keep it out because I didn’t want to paint a less-than-flattering account of Bias. When he relayed that feedback, I groaned in disappointment at my memory lapse as well as my failure to seek Todd’s review of the commentary before submitting it to my editor. In fact, I had simply forgotten that part of our shared Len Bias experience.

It was no small thing to have slipped my mind, either. Offering a glimpse of his partying ways and even foreshadowing the circumstances of his eventual death would have done much to elevate the commentary’s context and insight.

For one thing, it didn’t take a detective’s mind to deduce that Bias was using Todd’s flashlight to sneak in through the woods that surrounded the camp to avoid being caught sneaking in after curfew.

Beyond that, relating the wee-hours side of Len Bias would have painted a much more rounded portrait of a 21-year-old man at the crossroads of great promise and an even greater capacity for self-destruction that would ultimately, and tragically, prevail.

On a side note: a few years later, I had the opportunity to meet Len’s mother, Lonise, as she spoke in Macon, Georgia, where I was an intern at the newspaper. My story was picked up by the Associated Press–the first time my work appeared over the wire service.

Related Posts:

When the Going Gets Tough…Stop Keeping Score?

PR As Hoops: Following Your Own Shot